Squatting for Health

Squatting For Health

You just graduated from physical therapy and are finally back to doing those things that keep you physically active, but that little thought inside your head is concerned about how you will continue to build on the progress you’ve already made in the clinic.

Incorporating strength training into your movement routine is a great way of staying active and helps train your body to keep doing the things that make you happy. Whether that be hiking, skiing, sports, rowing, climbing or picking up your grandchildren from the floor etc.

The squat is arguably the most popular exercise used by athletes and fitness enthusiasts alike and for good reason. The benefits of squatting include:

- Builds lower body muscle and strength

- Improves joint stability and posture

- Keeps you functional and flexible

- Increases bone mineral density

- Strengthens your core

- Reduces risk of injury

The squat can come in a lot of variations including style, depth, and technique. For the purposes of this blog, we will stick to basics on understanding the movement requirements for a traditional back squat so you can easily apply it at home or in the gym.

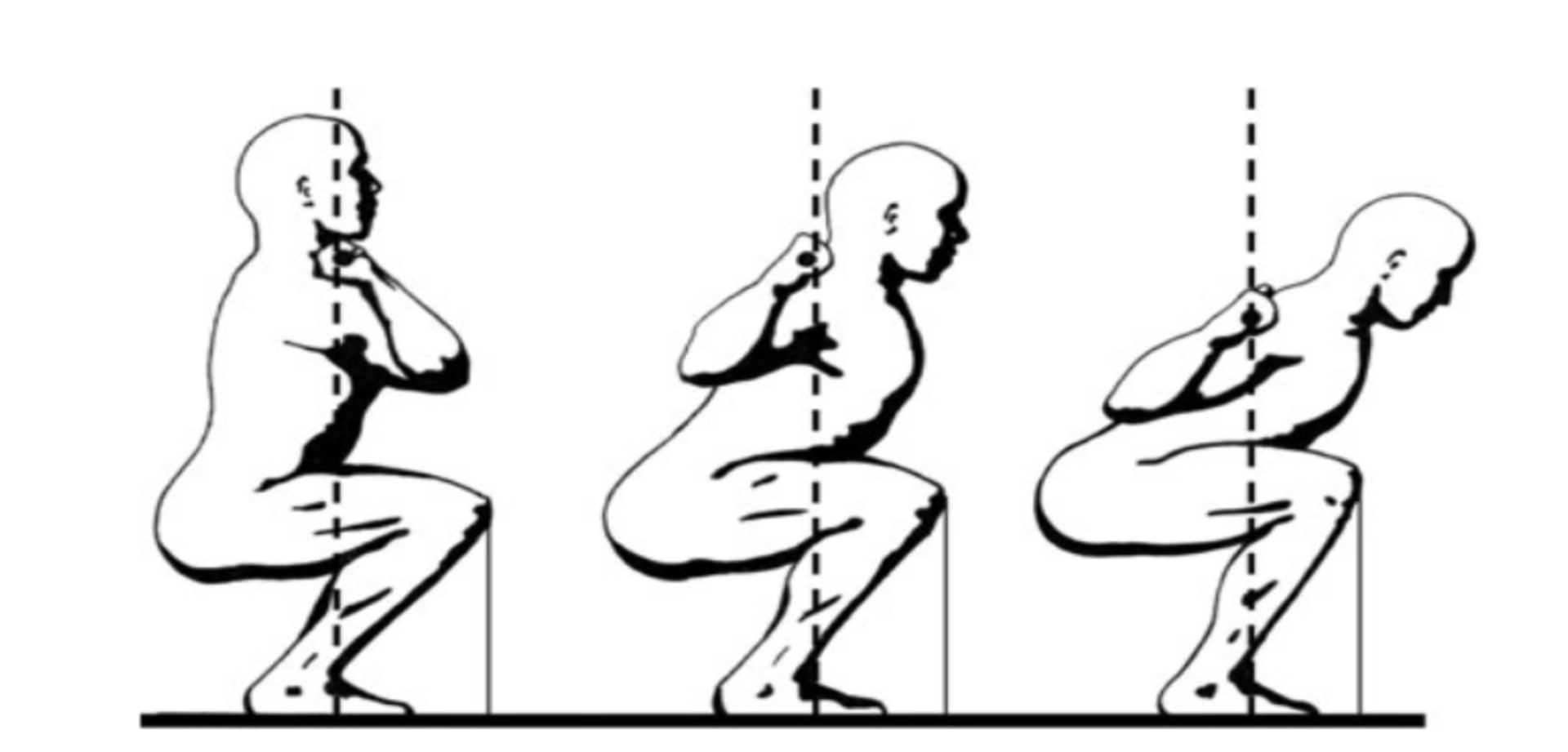

The primary joint actions that occur during the squat include:

- Eccentric (lowering) Phase

- Hip flexion

- Knee flexion

- Ankle dorsiflexion

Concentric (lifting) Phase

- Hip extension

- Knee extension

- Ankle plantar flexion

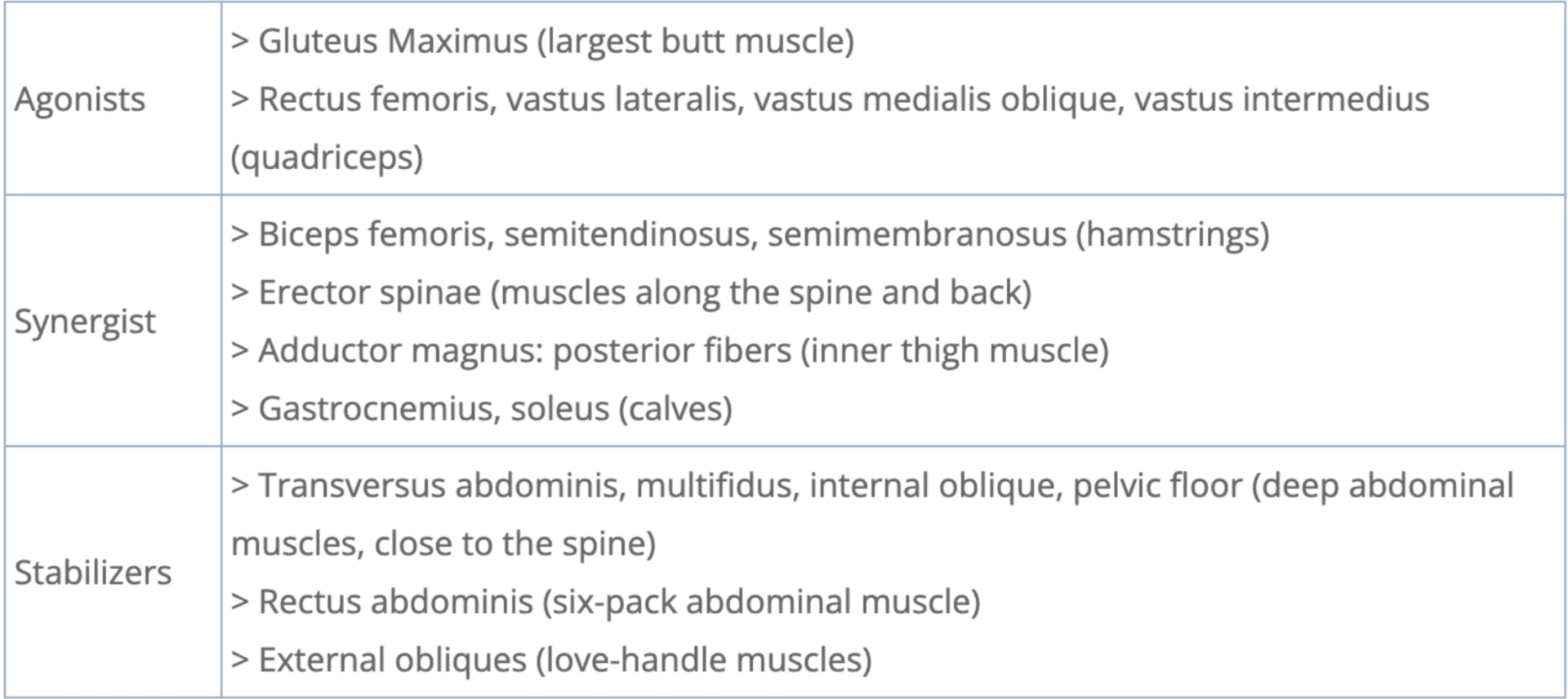

There are several muscle groups that help to power these movements. Below is a table that identifies these muscles, grouping them into their primary roles:

To perform a squat consider these fundamental steps

Squat Technique:

- Stance at shoulder width (toes 0-10 degrees pointed out)

- Brace neutral spine and maintain throughout

- Weight balanced at midfoot

- Hips and knees release together, squat straight down

- Knees track over or slightly outside of toes

- Hip crease descends below the top of the knee

- Maintain a neutral head position, gaze upward

- No change in spinal position throughout movement

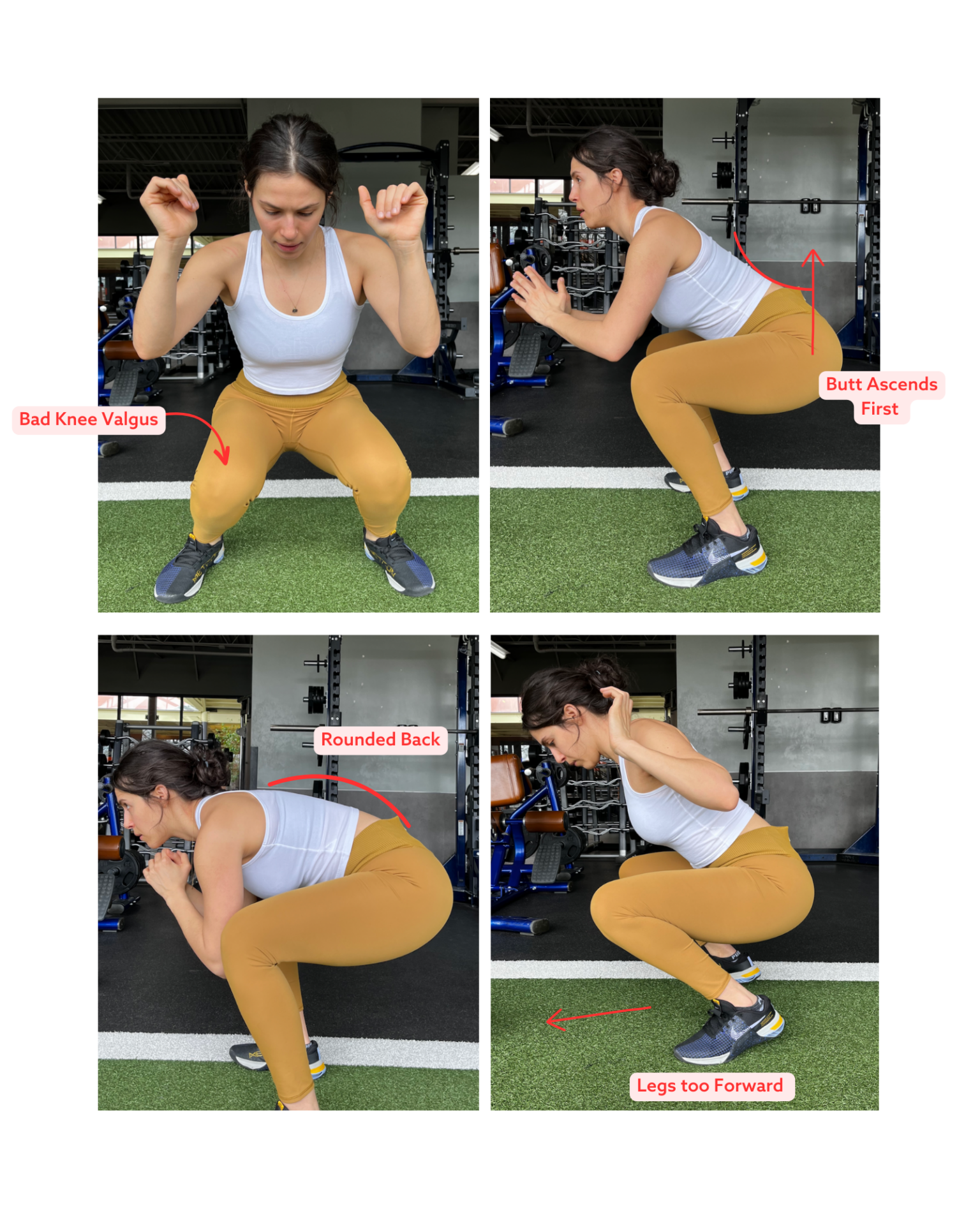

Common Faults:

- Drive your knees out to avoid them “caving” inward

- Make sure to maintain a neutral spine and avoid overextending your low back at the bottom of the squat as you start the ascent

- From the bottom of the squat lift up with your legs and avoid leading with your low back or rounding and losing the neutral spine

- Maintain your weight equally distributed onto your feet and limit shifting forward onto your toes on the way back up to avoid a quad dominant squat or, if using a barbell, to maintain a straight bar path

Breath:

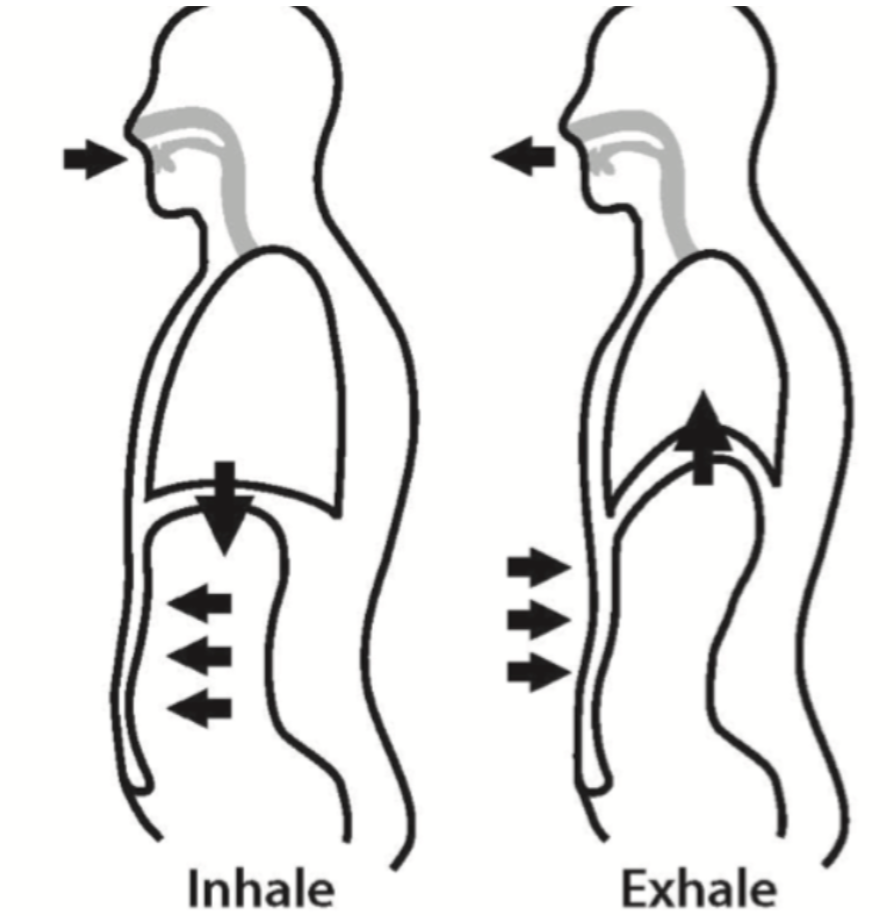

Another important thing to consider when squatting is creating intrinsic intra-abdominal pressure for stability of the spine. The pressure created with a diaphragmatic breath is higher than a chest breath. Consider inhaling and bracing at the top of your squat and maintaining that breath as you descend. As you begin to ascend from the bottom of the squat begin releasing air as if blowing it out of a valve “a.k.a. your mouth” A cue I often use with my clients is “blow as you go,” maintaining a controlled exhale.

Remember, there is not one way of performing a squat. Many individual forms will vary depending on the length of your femur or trunk, ankle or hip mobility, training specificity and personal goals, etc. If you find that you struggle with getting into a squat or feeling safe performing the movement, consider paying a visit to Stride Physio and consult with a physical therapist to help guide you through this movement. The benefits of squatting can have a profound effect on the quality of your movement and life!

References:

Almstedt HC, Canepa JA, Ramirez DA, Shoepe TC. Changes in bone mineral density in response to 24 weeks of resistance training in college-age men and women. J Strength Cond Res. 2011 Apr;25(4):1098-103. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d09e9d. PMID: 20647940.

Hagen Hartmann, Wirth Klaus, Kluesemann Markus. Analysis of the Load of the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load. Sports Med. 2013. Doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0073-6.