Optimal Biomechanics of the Double Kettlebell Swing

By Laurie Gribschaw, DPT, ATC, PRC

Seattle is a swingin’ town when it comes to getting and staying fit with kettlebells. Knowing how to use proper body mechanics will keep you safe and improve your performance outcomes. This article examines the anatomical and functional demands of the double kettlebell swing in sagittal plane of the body (front/back sides).

The double kettlebell swing (see video) is an exercise that requires mastering the hip hinge through dynamic control of the core while propelling through the hip extensors (gluteals/hamstrings). Its value reaches across not only the fat burning potential with cardiovascular health, but functional strength to lift and move a weight quickly through proper form while stabilizing the spine. As a sports and orthopedic physical therapist, I love this exercise for so many reasons: heavy emphasis on breath control, following a rhythmic pattern, finding/feeling the ground for centering of the body and pure strengthening of the core with gluteals and hamstrings. I also love the blend of two worlds that share so much overlap: optimizing the body for athletic performance, and expert coaching from a trained Kettlebell instructor. For the sake of our discussion here, Strong First is the school where I received and continue to pursue my Kettlebell training. When a qualified Kettlebell instructor notices that drills are unable to remedy issues related to an ineffective or inefficient swing, the next step can involve referral to physical therapy to identify and correct biomechanical concerns. When these biomechanical inefficiencies exist during the explosive swing, they can lead down a road of compensation patterns, imbalanced muscular production, and ultimately overuse injuries.

So what are the biomechanics needed to execute the Strong First double kettlebell swing? Because the double-handed grip is a symmetrical motion, the primary movement in the body is the forward and backward motion of the hips, placing the greatest demand for stability in the sagittal plane. The swing mimics a jump that doesn’t leave the ground, so we have a large need for unimpeded propulsion from the posterior chain of the hip, (the muscles on the back of your thigh) while keeping the spine and pelvis in a neutral position via strong core control.

Below is a breakdown of some of the needs required to keep spinal stability throughout the entire swing:

The Thorax:

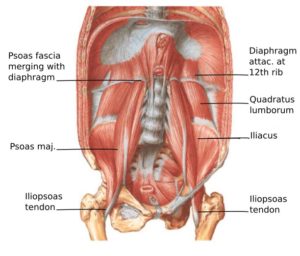

The ribcage and diaphragm are critical structures and their optimized function is key for core performance. The diaphragm must achieve and sustain a domed position, via lowering the front of the ribcage down and in, thereby avoiding any rib flaring. This ribcage position needs to be maintained in order to produce resting tension of the deep core musculature (i.e., internal obliques and transverse abdomins), thus protecting the spine. Posterior ribs, or the backside ribcage, must be mobile enough to enable inhalation so as not to perform a ‘belly breath’ during a heavy loaded activity. Belly breathing in this case would lengthen or weaken the core, promoting spinal instability. Likewise, use of the neck muscles for breathing would also compromise proper activity of the shoulder blades for support. Mid-thoracic (think bra line for us ladies) mobility into extension is paramount to allow proper latissimus engagement to connect a secured kettlebell to the torso. Ultimately, proper mechanics in the thorax allows us to breathe efficiently, pack our lats effectively, and promote ‘stacking’ of the torso on pelvis for a strong core during performance of the kettlebell swing.

Image credit: Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy

The Pelvis:

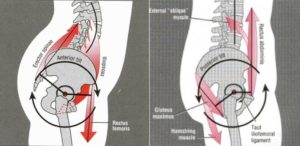

Notice in the above picture how many shared muscular attachments there are between the thorax and pelvis, especially the psoas and quadratus lumborum. A discussion regarding optimal pelvic and hip mechanics must always address the ribcage as it is so integral to maintaining proper length tension relationships of the muscles! So many of my clients will notice immediate improvement in hip extension following diaphragmatic breathing drills due to these shared muscular attachments. The pelvis must maintain a neutral position during the swing to optimize gluteal/hamstring muscle power; i.e. avoiding excessive posterior or anterior pelvic tilting. As pictured below, the pelvis must stay in neutral to promote optimal control of the spine via the hip extensors and deep abdominal muscles and avoid excessive arching of the lower back. When the pelvis and thorax are stacked effectively, then a hip has adequate support of its anterior ligaments, and has unimpeded motion into hip extension upon returning from the hinge position. If the anterior pelvic tilt remains present throughout the swing, it contributes to a forward shift in the center of mass, which places the back extensors, hip flexors, and quadriceps groups as the prime movers for the motion and can result in the swing inappropriately being a back and knee driven motion.

Image Credit: Google Images, TheDailyHealthPost.com

We know that the pelvis and thorax form the cornerstones of spinal stability given their shared muscular attachments of the deep abdominal muscles. The position of the pelvis is further supported by optimizing the hamstrings and gluteals while the ribcage is assisted by the serratus anterior, triceps, and lower trapezius. All of these muscles should be in ideal positions to support the kettlebell swing movement and preserve effective alignment in the sagittal plane. Given the highly repetitive nature of training the swing, it is paramount to include a warm up that involves breathing to restore an exhalation, or domed state of the diaphragm.

Many of us are training following lengthy periods of stationary postures while at work, with ergonomics that may not be customized for our independent structures and body metrics. This can easily place us in postures like the anterior pelvic tilt that would greatly decrease the efficiency of our kettlebell swing. If we continue to train in faulty sagittal plane positioning, then we can easily get postural shifts into the frontal, or side to side plane, with asymmetrical use of muscles. This can lead to developing compensatory flexibility/loosening in the extremities, such as in the pelvis or anterior hips. The compensations eventually result in spinal strain due to irregular back movements while returning to a midline position. Signs of this inefficient swing can show up as heightened back tension, anterior knee pain, hip impingement or a variety of maladies. One of the more common compensations I see during the swing are over-active quadriceps muscles during an attempt to utilize a knee extension strategy due to loss/tightness into hip extension. Another cheat is an overuse of the back extensor muscles, which prevents the individual from reducing their anterior ribcage flare, resulting in overloading the lower lumbar spine into excessive extension.

Every individual has their own unique structure and story which can contribute to needing a specific, customized warm up for their desired activity (you’ve probably realized everyone can benefit from breathing by now since ribcage mobility is paramount to success). This also can affect the way you would perform your swing; I thoroughly support seeking a qualified movement specialist, such as a physical therapist, to ensure your system has efficient biomechanics as a means of injury prevention, and performance optimization. Either way, the partnership between physical therapist, strength coach, and athlete is one that can foster health and injury-free longevity in your desired activity.